Since the start of her artistic practice over a decade ago, Nadia Ayari has engaged painting and the history of its development with marked intensity and seriousness. Adding to the complexity that one finds in her usage of the medium is her subject matter, which is not easily decipherable; figural but somehow abstracted and simultaneously sensual with tinges of the grotesque. Her “figures” are outwardly peculiar, psychologically laden, and allegorically political—a combination that is accentuated by the painterly force with which they are rendered if one considers the artist’s stirring palette, her cinematic usage of space, and the densely executed brushmarks that add a textured dimensionality to her canvases.

The interview below, which quickly turned into a dialogue, attempts to outline the formalism central to Ayari’s work while also providing a glimpse into the theoretical approaches and conceptual aims that have been crucial to her evolution as a painter. The following conversation was conducted via email over the span of several months, beginning in September 2013, and benefitted from studio visits with the artist in New York City (where she is based) and Dubai (where she is currently in residence as part of Art Dubai Projects).

Maymanah Farhat (MF): I would like to begin our discussion of your work by first noting the time and context in which your “creatures” (for lack of a better word) emerged. The timeline of your career documents your move from Tunisia to the United States in 2000, where you later received an MFA from the Rhode Island School of Design.

When did these anthropomorphic figures enter your compositions? Which specific protagonist initially threw open the door to their parallel world? Where exactly did they come from, are they characters of the imagination or composites of real-life personalities?

Nadia Ayari (NA): About two years into my art practice I started painting imaginary portraits. I think those were the first creatures to forcefully come to the foreground. I remember being impressed by their narrative powers and in retrospect I think this was the first transition to my current mode of making. Previous to that, I had been struggling to negotiate my political commitments with the abstract works I was painting.

Two years later, while I was in graduate school, the door ‘flung open’ as you say. The eyeball, finger, and tongue were the three protagonists that brought this on. I was so engaged with these characters that it was as if the work was making itself—all I had to do was show up. Those paintings are in some ways similar to the work I am making now. But I was then very technical about their significance, assigning meaning to each protagonist and contextualizing the work accordingly. I discussed the eyeball as a stand in for our conscious experiences and the fingers as a representation of our social selves. I do not recall the exact language I used to talk about the tongue but it probably had to do with sexuality and the Id.

The symbolism of the protagonists I use today—the fig, the tree, and the blood—is not precise. This abstraction is likely the consequence of having transferred political weight from the work onto its supporting structures.

[Pouring (2013). Image copyright the artist.]

[Pouring (2013). Image copyright the artist.]

MF: The ghost of American painter Philip Guston seems to guide examples of your early work, yet in closely looking at the paintings that he is most known for, technique-wise you are worlds apart. Your brushstrokes are more deliberate, meticulous, and tactile while your palette is very Mediterranean with variations of white, pink, grey, black, and blue. Guston was consumed by pinks and flesh tones and embraced the loose brushstrokes that distinguished Abstract Expressionism.

Can you walk us through how you took apart his aesthetic in first establishing the forms that your figures would take? Were there formal and conceptual aspects of his painting that originally provided answers?

NA: Guston’s post-1968 works answered my doubts about painting’s political charge and his mid career transition back to figuration exemplified artistic commitment. He became a sort of art ‘father.’ I would sit on the floor of my studio combing through the catalog of his most recent retrospective. I found the KKK, Studio and Musa paintings particularly compelling. More than the manner in which they were painted, I was astounded by how they held together as paintings. Those works should not be ‘good’ but are undeniably so. I was reminded of this a few months ago at McKee Gallery in New York. Some of his pieces are simply astonishing—full of urgency and grand momentum. And they are holding up so well; the painting ideas and their execution are so fresh.

My enthusiasm may hint to how enamored I was with his work as a young painter. It also may explain why I did not question derivative-ness when I started painting eyeballs. I was excited and wanted to consume his work and make it my own. It took me about five years to paint my way out.

MF: The Guston connection is also interesting from the perspective of how narratives can develop and are eventually altered through form. His initial paintings of Klu Klux Klan figures were obviously engaged in early American modernist painting while he was first coming into art in California, specifically Social Realism, as the influence of the Mexican Muralists had taken over and the WPA movement was directing American schools. Later as the emphasis on texture and brushwork of late modernist painting coincided with his development, these figures became less menacing and overbearing and more pathetic, one might even say tragic and comical. Of course Guston was haunted by these characters his entire life and many relate it back to his early awareness of anti-Semitism and racism and its extreme manifestations in the United States. Thinking of this transformation, one wonders if form was largely responsible for this shift since such elements are part of the symbiotic relationship of art to a given environment and, by extension, to the politics of that setting.

During our studio visit, you touched on how much of your work transitions from one piece to the next, how narratives are carried over the course of several successive paintings, and how at certain points a break occurs (or appears), almost in a violent way. I am thinking specifically of the ominous cog-head figures appearing in Procession, Discourse, and Wildflowers. At the time of our visit there was a small yet powerful and wholly present painting inconspicuously resting against a wall that seemed to signal the end of this series. Those works are outwardly political and sometimes erotic, and then suddenly with this small painting that specific narrative and all its tales of corruption, greed, vanity, conspiracy, and struggles for power are brought to an end. Can you talk about that process a bit and that series in particular?

.jpg) [Date (2009). Image copyright the artist.]

[Date (2009). Image copyright the artist.]

NA: You hit on something very important in discussing form and the role it played in Guston’s transitions. I agree that the varying aesthetics he used at different times in his career had everything to do with the socio-political landscape. When he uncovered his figurative paintings at Marlborough Gallery in 1968 he was among other things forcing the rarefied New York scene to deal with images of the Civil Rights movement. He also, in what seems to have been a consequence of that act, freed himself from the confines of Modernism to offer the art world an iteration of American Post-Modernism.

In 2008-2009, I decided that an explicit narrative might synthesize the multiple stories I was following in the news. The US presidential elections came and went, the recession was in full swing, and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan continued. So, I invented two characters: a gun-head politician and a blue-eyed civilian. For approximately a year and a half, I explored their courtship while shifting their political settings. This story begins with a small painting called Date in which the gun-head shows up at the eyeball’s door with a bouquet of pink flowers. The series ends with Love, the painting you saw in my studio. In it, the politician finally ‘wins’ and he is shown puncturing the civilian’s round blue and white head with his long black muzzle.

.jpg) [Love (2009). Image copyright the artist.]

[Love (2009). Image copyright the artist.]

MF: Your most recent series, which was shown at The Third Line gallery’s Project Space in September, introduces a new set of characters and a more sensual, inviting setting, yet the themes that you have outlined for these paintings, “love, politics, and indoctrination,” are very much aligned with the psycho-social representations that seem to inform all your work. How, in your view, are these subjects linked? How do they come together with such intensity through the creative process?

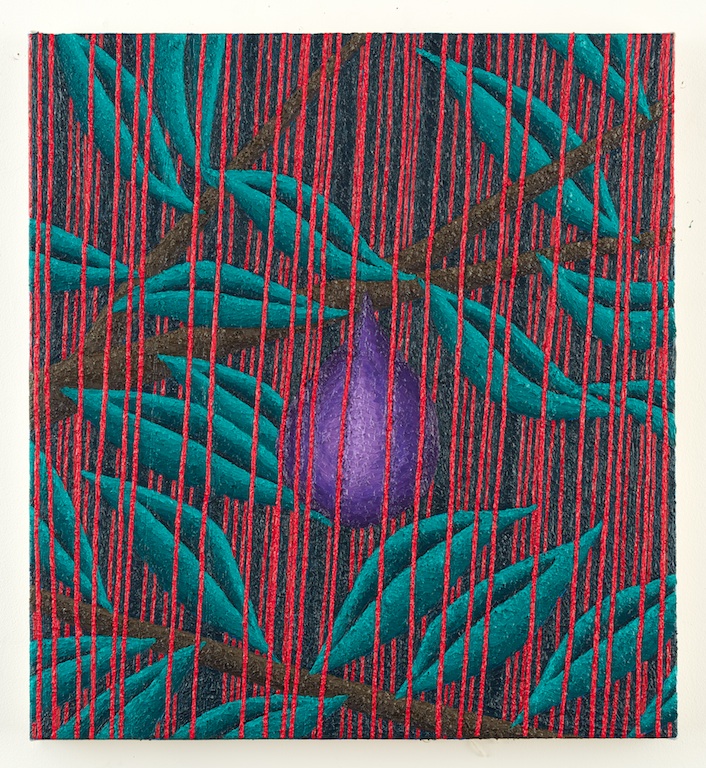

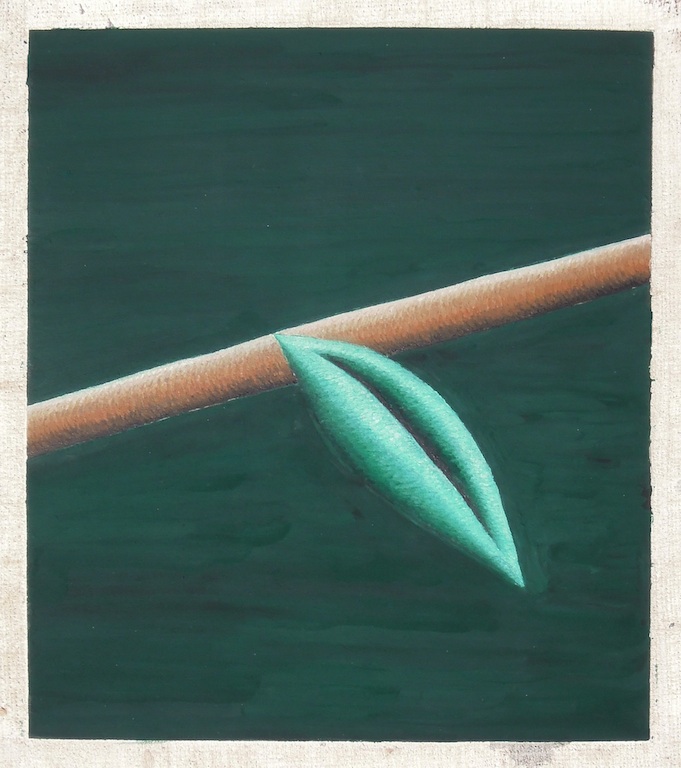

NA: The new work is most definitely a continuation of the same narrative but I have to admit that how these forms meet up time and time again is a mystery to me. I approached the new paintings with the simple desire to delve into a specific set of characters. A painting of a composite fig and olive tree titled Balcony from 2011 offered something new. For years, I had been working with the pink/black and blue/white eyes. That is how I tackled the fig and the tree. When the blood came into the paintings as a recurring protagonist and I found myself making saturated green/red paintings—a nightmare color combination—I knew something particular was happening. I quickly became aware of the formal challenges the paintings presented—from their complimentary colors to their obsessive textures and I trusted the project would engage me for some time.

I thought a lot about time while making these pieces. The events in the paintings don’t represent a singular moment in a narrative but are a metaphor for time itself. In Fountain the viewer is faced with the concept of a cadmium cascade. The jet of blood is represented in its full-fledged emergence (not in its initial burst or final throbs).

[Fountain (2012). Image copyright the artist.]

[Fountain (2012). Image copyright the artist.]

MF: It is interesting to note that the introduction of the fig—a small, fragile delicacy—takes on “the tension between political reality and sensual fiction,” as you have described, with such visual force, especially in moments when it splits itself open and releases. Each canvas in the series functions almost as a snapshot of a larger scene, one fig begins the process of transcendence by opening while another timidly sits as the downpour of another’s realized release and resulting magma blankets it. The site of tension is thus established as the space between this release and the lush vegetation of the tree, which is the series’ political backdrop or rather, the hierarchical structure from which these specific characters must break free.

In a previous conversation you mentioned that your brother, who is also working in visual culture through film, noted the color of the fig is the same shade of purple that was associated with Ben Ali’s regime through its official campaigns. With this in mind, how much of what has been taking place in Tunisia creeps into your work? The visuals of this new series certainly speak of the explosions of dissidence that have poured onto streets in so many parts of the world, first in Tunisia and now in Turkey. The Fountain and the Fig appears to confirm what you were already predicting in the series that came before, in terms of a build up that was certain to explode.

NA: It is hard to say how much the work is related to a national landscape. I followed the uprising in Tunisia very closely so when my brother associated particular political significance with the work, I knew that his interpretation had its place. But that is not how I read the images. The paintings focus on instances of the political structures that surround us by presenting allegories of dominance and desire. And though their sexuality is explosive, the viewer is free to contextualize the paintings within a more specific political landscape.

MF: Returning to the subject of form, your Without Walls series (2012) appears to place the role of art as it unfolds through exchanges of social engagement as its top priority. After creating a series of small, intimate frescoes, you traveled through New York City neighborhoods and placed these works in front of humble places of worship. What about fresco painting, its history, its known uses, and its formal properties signaled the conceptual framework of this project? In some ways, the use of the medium began as a people’s art during the Italian Renaissance, although it was supported by church patrons, and was later revived as such with deep political sentiments in early twentieth-century North America.

NA: The Without Walls series began when I was asked to produce a piece in Thessaloniki. I had just learned how to make portable frescoes and was drawn to the idea that I could make contemporary frescoes that could be made indoors then moved outdoors and I decided to photograph them in front of ancient architectural edifices. As I began to execute the project and realized how fragile the paintings on plaster were, I became fascinated with their accumulating cracks and erosions. One of the medium’s properties and the main reason it was so widely used to adorn public and private interiors is its stability. Wet pigment applied on a mix of lime and sand calcifies to become part of the wall or ceiling. But when removed from architectural structures and placed on portable surfaces (I used burlap on wood panels) the hardened plaster turns fragile. This is a great analogy for the painting canon: as soon as one removes that history from its armature, it falls apart.

MF: Fast-forwarding to February 2014, several months after we first began our conversation, you are currently completing a new fresco installation during a residency at Art Dubai. Two sets of frescoes will appear in the lavatories of the fair’s venue, both of which will be strategically placed and feature various manifestations of your figs. Can you describe this project in detail, as it will appear and exist as a site-specific installation, while also reflecting on how the project came about? Did you begin the residency knowing that you would work in fresco again after having just completed a new series of paintings?

NA: How appropriate that in the last question I answered before heading to Dubai, I refer to painting armatures. I have been thinking a lot about those lately. The piece I am putting together for Art Dubai Projects is a sculpture that will double as an armature for a group of paintings I have been working on here. Situated in the lavatories outside of the fair’s contemporary venues, it will consist of two freestanding walls: one in the women’s, the other in the men’s. Each will be positioned to parallel the respective bathroom’s bank of mirrors. On the face of the wall that reflects in the mirror will hang a set of frescoes. The piece’s title is Selfie Booth, WC.

[Face (2014). Image copyright the artist.]

[Face (2014). Image copyright the artist.]

I was initially going to do something quiet, which included the bathroom as a possible site. Then I visited the venue and remembered that a fair is no place to be subtle. Given the non-commercial context of my piece, a constructive critique of art consumption’s current aesthetics seemed possible. Let’s see what happens when it is up 19 – 22 March.

After being so immersed in my slow oil painting process, I wanted to reengage with fresco for the three months of the residency. It felt like the time to shift and generate a number of images over a short period. I was secretly wishing that this would unlock some new characters: a sky or a horizon. But as you saw in the studio, it worked a different way. The images are so sparse that the protagonists transformed: the branch became the horizon, the blood disappeared into green, and the pictorial space swelled.

![[Nadia Ayari`s \"Love\" (2009). Image copyright the artist.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/NadiaAyariLove2009.jpg)